What is Bitcoin?

In a traditional financial system that depends heavily on intermediaries and trust based costs, Bitcoin has become a starting point for understanding the idea of decentralized finance. Exploring its definition, operating model, core mechanisms, value foundation, and practical limitations helps form a clearer and more structured view of this new financial paradigm.

What Is Bitcoin?

Bitcoin is a decentralized digital currency built on blockchain technology. Its core objective is to enable global value transfer and ledger recording without the need for a trusted third party.

Unlike traditional electronic payment systems, transaction verification, record keeping, and publishing rules in the Bitcoin network are defined by open protocols and executed collectively by distributed nodes. No bank or clearing institution controls the system.

Functionally, Bitcoin is both a digital asset and a complete payment and accounting system. Structurally, it consists of transactions, blocks, a blockchain, nodes, and a consensus mechanism that ties everything together.

The Origins and Design Intent Behind Bitcoin

Bitcoin emerged in October 2008 when an author using the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto published a paper titled “Bitcoin: A Peer to Peer Electronic Cash System”.

The timing was significant. In the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, weaknesses in centralized financial institutions, high trust costs, and opaque monetary policies had become painfully visible. Against this backdrop, Bitcoin sought to answer a fundamental question: how can a trustworthy system for transferring value exist without centralized intermediaries?

From the outset, Bitcoin emphasized decentralization, censorship resistance, and rules that cannot be arbitrarily changed. These principles have deeply shaped its technological path and long term evolution.

Before Bitcoin, others had proposed similar ideas for decentralized electronic money. However, Bitcoin was the first cryptocurrency to achieve real world adoption. Tens of thousands of participants gradually formed a global community, laying the foundation for the broader cryptocurrency industry. Looking back, its emergence stands as a milestone in financial history. Over time, numerous platforms supporting Bitcoin have expanded its practical use cases, including wallets, exchanges, travel services, online payments, and gaming.

Bitcoin transactions are secure, censorship resistant, pseudonymous, and not limited by national borders. This makes it a potential alternative payment method, especially in regions with limited access to traditional financial services. The total supply is capped at 21 million coins and cannot be increased under the protocol rules. Because of this fixed supply, Bitcoin has increasingly been viewed as a store of value and is often referred to as digital gold. Those who purchase Bitcoin often share a belief in the long term value of a decentralized and digitally native asset.

How Does the Bitcoin Network Work?

The Bitcoin network is composed of nodes distributed around the world. Each node independently verifies transactions and blocks.

When a user initiates a Bitcoin transaction, it is broadcast across the network. Nodes verify its validity, checking, for example, whether the sender has sufficient balance and whether the digital signature is valid.

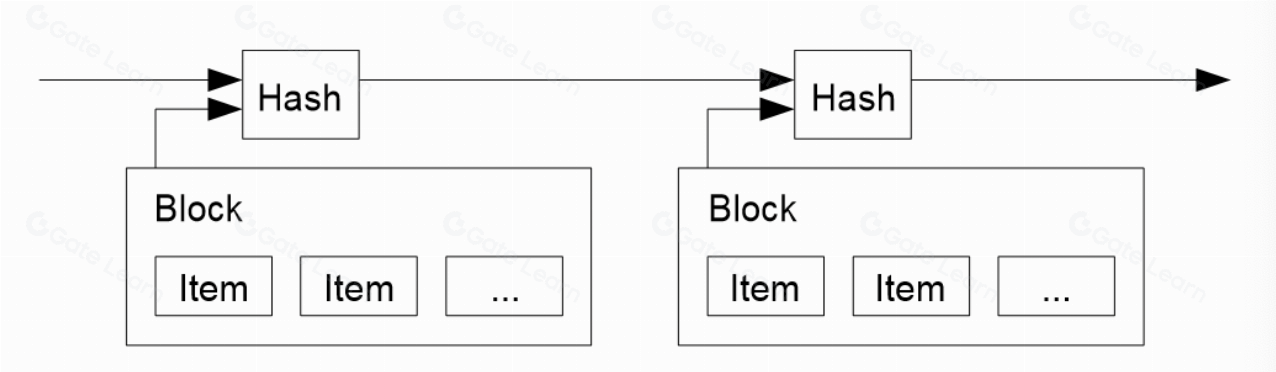

Verified transactions are grouped into blocks and written to blockchain through a consensus mechanism. The blockchain functions as a chronological ledger, recording every transaction since the system began.

Long before digital ledgers, the Rai stones of Yap Island recorded ownership by crossing out the previous owner’s name and writing in the new one. The idea of maintaining a public record of ownership predates modern civilization.

Within the Bitcoin network, each transaction transfers coins by updating the ledger and using digital signatures. The transaction references the previous one and includes the recipient’s public key hash, then is packaged into a block and broadcast to all nodes. Through collective verification, the network ensures the recipient receives the funds properly.

In a decentralized system like Bitcoin, the risk of “double-spend attack” must be addressed. Double spending refers to attempting to spend the same coins twice to deceive the recipient. The practical solution is a reliable consensus mechanism that ensures only one valid transaction history is accepted.

Bitcoin uses a timestamp server. This server groups multiple transactions into a block, calculates a hash, and attaches a timestamp. Each timestamp includes the previous one, forming a chronological chain that proves the existence and order of data. This structure prevents double spending and makes past records increasingly difficult to alter.

These blocks form a chain that grows through proof of CPU work, which is the task performed by Bitcoin miners.

Bitcoin’s Consensus Mechanism and Mining Principles

Bitcoin’s Consensus Mechanism

Proof of Work, or PoW, is the foundational consensus mechanism used in early blockchain systems such as Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Litecoin. It ensures ledger consistency and resistance to tampering.

In simple terms, all network participants compete to solve a cryptographic puzzle. The first to find a valid solution earns the right to add a new block to the ledger and receives a corresponding reward in newly issued cryptocurrency.

The concept builds on Adam Back’s Hashcash system, originally designed to combat email spam by requiring computational effort. Bitcoin adapted this idea to secure a distributed timestamp server for peer to peer transactions.

In Bitcoin, the block hash is a 256 bit binary number produced by running the Secure Hash Algorithm (SHA-256) twice. A predefined target difficulty determines how small the resulting hash must be. Since each hash output is effectively random, each number can be 0 or 1, there are 2^256 (2 to the power of 256) possible combinations. The more leading zeros a hash contains, the smaller its value. To be valid, a block’s hash must be below the target difficulty.

The miner who first computes a valid hash broadcasts the corresponding block. Once verified by other nodes, it becomes part of the blockchain, and miners move on to compete for the next block. Through this continuous process of verification, broadcasting, and record keeping, all nodes maintain an identical and constantly updated ledger.

The target difficulty adjusts automatically every 2016 blocks. Based on the network’s total computing power, the system aims for an average block interval of about ten minutes. Miners with greater computational capacity have a higher probability of finding a valid hash and earning the block reward. This competitive process defines Proof of Work.

Proof of Work also addresses the risk of majority based manipulation. Decision making power is effectively tied to computing power. The longest valid chain represents the accepted transaction history. If most computing power is controlled by honest participants, their chain will outpace any competing chain. For an attacker to succeed, they would need to redo the Proof of Work for all subsequent blocks, and the probability of catching up decreases exponentially over time.

Bitcoin Mining

Bitcoin mining is the practical implementation of Proof of Work. Using specialized hardware, miners continuously perform computations to validate transactions and secure the network. In return, they receive transaction fees and newly issued bitcoins as rewards.

Miners are located worldwide, and no single entity controls the network. The process is often compared to gold mining. However, unlike physical gold extraction, Bitcoin mining is a temporary issuance mechanism designed to distribute new coins while incentivizing network security.

To earn rewards, miners aim to maximize their computing power in order to increase their chances of solving the cryptographic puzzle first. The miner who finds a valid hash broadcasts the block and competes for the next one.

Mining requires enormous computational effort, often involving billions of hash calculations per second. As more miners join in pursuit of rewards, the network’s difficulty rises accordingly. Roughly every ten minutes, the system recalibrates to maintain its target block time.

Proof of Work ensures that blocks are added in chronological order. Reversing or altering past data would require recomputing the Proof of Work for all subsequent blocks, which is practically infeasible. If miners receive two competing blocks at the same time, they temporarily follow the one they saw first but switch to the longer chain as soon as it emerges, ensuring synchronization across the network.

Bitcoin’s Issuance Mechanism and Supply Design

Bitcoin’s issuance rules are embedded directly in its protocol. New bitcoins are created as block rewards, and the reward amount decreases over time.

This mechanism eliminates the possibility of arbitrary monetary expansion. The total supply is capped at 21 million coins. This issuance structure gives Bitcoin a predictable monetary policy.

Here are the key points of the Bitcoin issuance mechanism:

| Item | Design Description |

| Issuance Method | New bitcoins are issued as block rewards through mining. |

| Maximum Supply | Capped at 21 million coins. |

| Block Reward | Halves approximately every 210,000 blocks. |

| Block Time | A new block is produced on average every 10 minutes. |

| Rule Changes | Require network wide consensus and cannot be unilaterally altered. |

Where Does Bitcoin’s Value Come From?

Bitcoin’s value is not derived from government backing or physical asset collateral. Instead, it rests on several structural factors, including scarcity, network security, decentralization, and user consensus.

The fixed supply design gives Bitcoin characteristics similar to scarce assets. Its decentralized network reduces single points of failure and censorship risk. As participation grows, both its utility and security increase, creating network effects.

In certain economic environments, Bitcoin may also become part of broader asset allocation discussions, which can influence its price performance.

Historical Bitcoin price review:

| Year | Price | Primary Driving Factors at the Time |

| 2010 | 2 pizzas | On May 22, 2010, software engineer Laszlo Hanyecz posted on the Bitcointalk forum offering 10,000 bitcoins in exchange for two delivered pizzas. This transaction became the first widely recognized real world Bitcoin purchase. |

| 2011 | 1 USD | In early 2011, the Electronic Frontier Foundation in California announced that it would accept Bitcoin donations. Over the following months, growing visibility helped push the price higher. In February, Bitcoin surpassed 1 USD for the first time and later surged to 30 USD on Mt. Gox, then the largest Bitcoin exchange. |

| 2013 | 1,100 USD | On November 28, 2012, Bitcoin experienced its first block reward halving. Reduced supply, combined with renewed donation acceptance by the Electronic Frontier Foundation and broader market momentum, contributed to a historic rally. After starting the year around 13 USD and enduring a sharp 70 percent correction, Bitcoin reached a new high of 1,100 USD by year end, making 2013 one of its highest return years. |

| 2017 | 20,000 USD | A surge in altcoin speculation, significant retail participation, and expanding public awareness of Bitcoin drove rapid price growth. In December 2017, Bitcoin surpassed 20,000 USD. |

| 2021 | 69,000 USD | Loose macroeconomic conditions, increased institutional allocation, and growing recognition of digital assets contributed to Bitcoin reaching approximately 69,000 USD. |

| 2025 | 120,000 USD | In 2025, Bitcoin exceeded 120,000 USD. The rise was widely attributed to slower post halving supply growth, greater institutional participation, supportive macro liquidity conditions, and the strengthening long term network effect. |

Advantages and Disadvantages of Bitcoin

Like most transformative innovations in history, Bitcoin and blockchain technology provoke strong and divided opinions. Critics argue that Bitcoin is a speculative bubble that has caused environmental damage and significant financial losses. Supporters view it as a remedy for inequality and corruption within the existing financial system, offering genuine economic autonomy. Below are some of its advantages and disadvantages.

Advantages of Bitcoin

Cannot be created arbitrarily. The supply is capped at 21 million coins and can only be obtained by contributing computational power. No one can issue additional bitcoins to dilute holders.

Decentralized. The network is supported by miners worldwide and runs automatically according to open source code. Anyone can operate a node, yet no individual or institution owns or controls the network, in sharp contrast to centralized monetary systems.

Secure. Proof of Work and the vast computing power of miners protect the network. To carry out a double spend attack, an attacker would need to control more than 51 percent of the total computing power. The economic cost makes such attacks highly impractical. To date, Bitcoin remains the most secure cryptocurrency.

Peer to peer payments. Transactions occur directly between individuals without third party approval. Accounts cannot be easily frozen or censored, giving users control over their property.

Borderless usability. Bitcoin can be used for international transactions at any time. While acceptance varies by country, exchange channels generally exist, making it a globally accessible currency.

Portability. As a digital asset stored on the blockchain, Bitcoin can be secured with hardware wallets the size of a USB device, software wallets on mobile phones or computers, or even a paper record of private keys.

Transparent and immutable ledger. All transactions are publicly recorded and can be audited using blockchain explorers. Once confirmed, transactions cannot be reversed, and altering historical records is nearly impossible.

Scarcity and resistance to inflation. The 21 million supply cap is hard coded and cannot be modified under normal circumstances. Block rewards halve approximately every four years, and new issuance is expected to cease around 2140. This predictable scarcity gives Bitcoin deflationary characteristics similar to electronic gold.

Long term appreciation potential. As the first and most influential cryptocurrency, Bitcoin often serves as a market benchmark.

Disadvantages of Bitcoin

High mining costs. Maintaining network security requires substantial energy consumption. In 2021, Bitcoin mining consumed 138.53 terawatt hours of electricity, exceeding the annual electricity usage of some countries such as Argentina and Ukraine.

Environmental impact. In 2021, operating the Bitcoin network was estimated to produce 77.27 million tons of carbon emissions. Hardware depreciation also generated approximately 34,570 tons of electronic waste, comparable to the annual small electronic waste of the Netherlands.

High volatility. Despite being the largest cryptocurrency by market value, Bitcoin’s price fluctuations remain significantly more dramatic than those in traditional financial markets, exposing investors to large swings in asset value.

Slow and sometimes expensive transactions. Bitcoin processes an average of about seven transactions per second. Compared with payment networks such as Visa, which can handle around 2000 transactions per second, this is relatively slow. Transaction fees can also fluctuate sharply during periods of market congestion and have at times exceeded 60 US dollars per transfer.

No refunds and limited recourse. Transactions are irreversible and do not rely on intermediaries. Users bear full responsibility for errors or disputes, and there is no built-in mechanism for chargebacks or account freezes.

Risk of asset loss. Control over bitcoins depends entirely on possession of private keys. If the private key is lost, access to the funds is permanently lost. Some early miners reportedly lost access to significant holdings due to damaged storage devices.

Limited practical use. Although Bitcoin functions as a store of value and medium of exchange, its price volatility makes it difficult to use as a stable unit of account. As of 2022, relatively few merchants directly accept Bitcoin, and users often need to convert it into local currency through exchanges.

Differences Between Bitcoin and Other Public Blockchains

Bitcoin’s decentralization is reflected in its distributed block production, resistance to rule changes, and strong safeguards against single entity control. By binding block creation rights directly to computational effort under Proof of Work, it allows participants to compete openly under transparent rules. This design prioritizes security and censorship resistance over transaction efficiency or feature expansion.

Compared with Ethereum, Bitcoin and Ethereum make different trade offs in their approach to decentralization. Ethereum expands blockchain functionality through smart contracts and greater programmability, pushing the boundaries of potential applications. However, its consensus mechanism, upgrade cadence, and governance model require more coordination. This provides flexibility in performance and ecosystem growth, but it also introduces greater complexity in system upgrades and rule changes.

Therefore, the difference in decentralization between Bitcoin and other public blockchains such as Ethereum does not lie in “whether they are decentralized”. Rather, it lies in how they prioritize decentralization relative to security and scalability. Bitcoin emphasizes rule stability and minimal trust assumptions, while other networks balance multiple objectives. These distinctions shape their application focus, ecosystem structure, and value narratives.

Summary

Bitcoin is a digital currency system built around decentralized value transfer. Its technical architecture, consensus mechanism, and issuance rules together form a distinctive crypto economic model.

Understanding Bitcoin provides insight not only into digital currency itself but also into the broader logic of blockchain technology and decentralized networks.

FAQ

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between Bitcoin and traditional electronic money?

Bitcoin does not rely on centralized institutions for record keeping. Its rules are enforced collectively by protocol and distributed nodes.

Q2: Can Bitcoin be issued arbitrarily?

No. Its issuance schedule and supply cap are written into the protocol and can only be changed through broad network consensus.

Q3: Is mining only about earning rewards?

The primary role of mining is to maintain network security and ledger consistency. Rewards serve as an incentive mechanism.

Q4: Is Bitcoin completely anonymous?

Bitcoin operates under a pseudonymous model. Transaction records are public, but addresses are not directly tied to real world identities.

Q5: Is Bitcoin suitable for all payment scenarios?

Not necessarily. Its design prioritizes security and decentralization over high frequency, small value payments.

Q6: Does understanding Bitcoin require a technical background?

A basic understanding does not require deep technical knowledge, but grasping its security and consensus mechanisms helps build a more comprehensive view of how it operates.

Related Articles

In-depth Explanation of Yala: Building a Modular DeFi Yield Aggregator with $YU Stablecoin as a Medium

The Future of Cross-Chain Bridges: Full-Chain Interoperability Becomes Inevitable, Liquidity Bridges Will Decline

Solana Need L2s And Appchains?

Sui: How are users leveraging its speed, security, & scalability?

How to Do Your Own Research (DYOR)?